"Warriorship does not refer to making war on others. Aggression is the source of our problems, not the solution . . . Warriorship in this context is the tradition of human bravery, or the tradition of fearlessness. The North American Indians had such a tradition, and it also existed in South American Indian societies. The Japanese ideal of the samurai also represented a warrior tradition of wisdom, and there have been principles of enlightened warriorship in Western Christian societies as well . . .

"Warriorship does not refer to making war on others. Aggression is the source of our problems, not the solution . . . Warriorship in this context is the tradition of human bravery, or the tradition of fearlessness. The North American Indians had such a tradition, and it also existed in South American Indian societies. The Japanese ideal of the samurai also represented a warrior tradition of wisdom, and there have been principles of enlightened warriorship in Western Christian societies as well . . ."The key to warriorship and the first principle of Shambhala vision is not being afraid of who you are. Ultimately, that is the definition of bravery: not being afraid of yourself. Shambhala vision teaches that, in the face of the world's great problems, we can be heroic and kind at the same time."

-- Chogyam Trungpa, Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior, 1988.

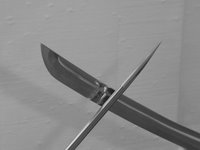

This really gets to the heart of bushido: the goal of being steadfast and tender at the same time. Ueshiba Morihei described his martial art, aikido, as the actualization of love. In iaido, we talk about the "life-giving sword." These apparent contraditions get to the heart of what is interesting about warrior traditions - we are fighters who are trying to be good people and to live in accordance with universal principles.

Nicklaus Suino teaches iaido and other martial arts at seminars throughout North America. Information about his seminars can be found at www.artofjapaneseswordsmanship.com. He teacher iaido, judo, and jujutsu at the Japanese Martial Arts Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan, home of the University of Michigan.